On the Counselor's Couch

The idea of counseling always freaked me out. I imagined counseling sessions to be very dark—teary, dramatic, sepia-toned, Victorian couches, coffee, and an old, stern-faced white guy with a beard, clipboard, and tweed jacket. Oh and rain . . . in my mind it was always raining outside when you went to counseling.

I thought counseling was the last stop for people before they went crazy.

I totally don't think that now.

Now I view counseling like I view oil changes for your car—an essential part of regular maintenance. I think everyone should go to therapy if they're able. (btw, I quickly learned it's cooler to call it "therapy" instead of "counseling." Kinda like saying "film" instead of "movie." Much fancier.)

Birmingham, Alabama, in the summer is like living inside a George Foreman grill. It's just all hot pavement, and you can't escape it.

It was one of those afternoons in the summer of 2006 when I pulled into the little wooded office park for my first therapy session.

I was 24 years old and had come here for one reason: To become straight.

Now, at this point in the story I must introduce you to the term "reparative therapy."

This is the kind of therapy designed to change, or "repair," someone's unwanted same-sex attraction. In a nutshell, reparative therapy is supposed to make a gay person straight, and it has a long and sordid history.

Over the years, reparative therapy has included really intense things like shock therapy, hypnosis, and even castration. In some cases, they would show the patient same-sex images and induce vomiting or pain in an attempt to connect a traumatic emotional response to an arousing stimulus. More modern iterations included various behavioral and cognitive treatments. I have a friend who went through some reparative therapy once, and part of it included a high school football coach teaching the guys about football and a Mary Kay consultant teaching the girls about makeup.

That really happened.

Thankfully, my friend is able to laugh about this now. And, shockingly, the football lessons didn't make him like girls.

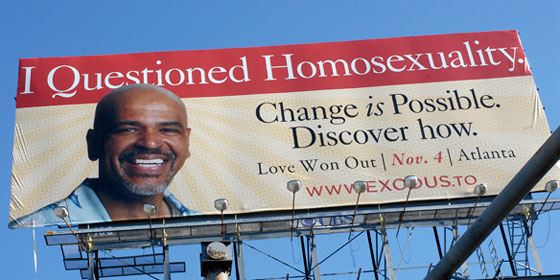

Back then, there was one big-name Christian organization that specialized in reparative therapy, Exodus International.

They created a big stir claiming that "change is possible." They even had some billboards like this:

As a Christian, I thought the concept of reparative therapy made a lot of sense.

In theory, if there's some unwanted thing in our lives, then it must be God's will to pluck it out. And we all know, that's what therapy is for—for plucking out the bad, fixing the broken, and injecting new hope. Back then, I was well-aware reparative therapy existed, but I was a bit skeptical. When I walked into that office that day, I didn't know this counselor's stance on that type of therapy. But I was definitely open to it.

Now . . . one more thing . . .

You must know the significance of this day for me . . .

Before walking in to that office, I had spent years grappling with this issue alone. I had said a million prayers asking God to change me. I had stood in so many prayer meetings and revivals and youth conferences with tears streaming down my face, begging God for a golden ticket into straightness. This was a big moment.

I have no idea how often heterosexual people think about their sexuality, but I thought about mine a lot growing up.

There's a big difference in thinking about SEX and thinking about your SEXUALITY, and I think maybe that's one difference in gay and straight people.

It's like the difference in thinking about pizza versus the pizza shop.

Straight people can just think about pizza and not ever consider where it came from. They've just always liked pizza just like everyone else. All they know is they think about tasty pizza a lot.

I think gay people spend a lot of time questioning where the pizza came from, wondering if it's safe to eat and why no one else's pizza looks like theirs. I spent a lot of time asking God to just shut the pizza shop down. I didn't want that pizza.

Yet while I was praying against it, I was simultaneously denying that same-sex attraction was a thing in my life. So I wasn't even sure the pizza shop actually existed.

Back then, I denied that same-sex attraction was an intrinsic part of me.

If anything, it was a clinger, a hanger-on, an invader, a tumor, a trespasser, a most unwelcome guest.

It's like the 1986 movie Aliens, where Sigourney Weaver fights off a horde of alien invaders inside her spaceship. Same-sex attraction was like one of those aliens—not part of the ship—just freeloading, wreaking havoc, and ripping people apart. So it was simply a matter of beating it back into outer space.

The problem with fighting same-sex attraction is that, unlike a 12-foot tall alien, it's invisible.

You know it's there. You see its effects. But you can't touch it, can't punch it, can't roast it with your flame-thrower.

You feel like a shirtless old man in whitey-tighties swinging wildly in the night at a ghost he swears he's heard a thousand times. And fighting an invisible enemy is something crazy people do. Being gay can make you feel crazy sometimes.

So pulling in to that therapist's office that day was a bold declaration for me . . .

This is real. It's an issue. I need help.

This would be a long journey. I knew that, and I was prepared. Walking in through those glass doors, I was nervous but confident. I knew God was with me.

I'll call my therapist Claire (name changed for anonymity). Claire was a very grandmotherly, older white lady . . . not what I was expecting.

She had a head full of curly, sandy blonde hair and the type of glasses you'd expect from a grandmother. Claire was soft-spoken and very kind which is maybe something they train in therapy school . . . idk. We small talked for a bit, and then she made the turn . . .

So what prompted you to come see me today?

It didn't take long for the floodgates to open again. I sobbed for the next hour as she asked question after question. Good therapists know the right next question to ask to keep you talking, venting, explaining.

People who have been to therapy know those early sessions are very biographical. It's basically just you telling your story while crying uncontrollably, and the therapist makes $125 an hour to nod and smile softly. Now, they earn their money much later in the process, but it takes a few sessions to get there.

Claire would eventually tell me that her specialty was with people dealing with a variety of sexual issues, including unwanted same-sex attraction. She told me she was a Christian herself, and that faith was part of her counseling strategy. She said I would benefit by meeting with a local recovery group in Birmingham. She said she could help me, but that she would never pressure me into doing anything I didn't want to do. I appreciated that.

This first session was great for me.

Letting unfiltered words flow from the heart into the ears of another warm, sympathetic body is in itself very therapeutic.

To confess. To be heard. To be understood . . .

The Bible says when we confess our sins to others, it brings healing. Each act of confessing, admitting, of unhiding, of unearthing a buried secret is a tiny declaration of freedom. Just giving language to our secrets has a way of weakening them.

Secrets are the opposites of plants, which need sunlight, water, and soil to grow.

Secrets thrive in dark, dry, neglected places. The more you neglect them, the healthier they get.

The more you hide them, the more they thrive. The darker you can make it, the bigger they grow.

And secrets hate being talked about. You can injure a secret with vulnerability, poison it with transparency, and handicap it with openness. They shrivel when discussed.

Of course, you can't solve all your problems just by talking about them, but it can loosen a secret's chokehold on your mind. I learned that in these early counseling sessions—a lesson that would get me through some rocky years ahead.

Claire and I continued to meet for weeks. We talked about my past, my childhood, my dad's death, my faith, my college experiences, my need for achievement. I rather enjoyed meeting with Claire.

But each time we met, I'd get a little more frustrated. I kept waiting on the BIG REVEAL. I kept waiting for Claire to finally pull me in close and whisper,

Okay, Brett, are you ready? Are you ready for the secret to becoming straight?

I had come to Claire to kill a vampire. I was ready for her to reach into her big black bag and pull out some garlic, a stake, some silver bullets, SOMETHING to kill the vampire inside of me. I was ready.

And we did some very therapy-ish things. Once she had me record myself talking into a microphone telling my story of sexuality. Then she had me listen to it over and over again. I don't know why I did that, but I'd do whatever she told me. In between sessions, I'd self-evaluate to see if any of it was working, if my attraction to guys was diminishing. It didn't feel like it, but maybe it just took more time.

Weeks turned into months and it was more of the same. I didn't feel any shift in my attractions.

I began to get more bold with Claire. I wanted to know what the prognosis was, what my chances of recovery were. And I began to listen closely to what she said and what she didn't say. She never said I could become straight. She never promised that. She hinted that some men she'd worked with had had a "diminishing" of their same-sex attraction. And she didn't talk at all about how, exactly, I would become attracted to women. I viewed it as a two-part problem: I needed to subtract the attraction to men and I need to add an attraction to women. Hell, I could live being attracted to men . . . it was an attraction to women that I was really after. But she never really elaborated on that, on how that process worked. I noticed.

After a few months I realized Claire had no silver bullet. And I realized that even a long drawn out counseling process was no guarantee.

I scoured the Internet trying to find the good fruits of reparative therapy—success stories—with little success. I enjoyed visiting with Claire, but I had cried all my tears, shared all my stories, and was running out of money. Instead of growing, my hope was fading. After a few months, I just quit seeing Claire. I just quit making the next appointment.

And in the months that followed, a thick fog settled over my life.

This was it.

This was my shot.

Counseling was the final option. It didn't work. Nothing changed. She didn't have answers.

My worst fear—an immovable attraction to men—was real. This nightmare was a stone-cold reality.

This football-playing preacher's kid . . .

Youth group role model . . .

Dedicated follower of Christ . . .

Motivator of fraternity men . . .

And campus ministry leader . . .

Was gay.

Before this, I had only known sadness.

Sadness is a temporary condition held in check by hope. And hope promises a better future, an eventual arrival of brighter day. But when hope leaves the building, despair walks in. And despair is something entirely different.

And so late one night, sometime back in 2006, my bedroom door creaked open. The shadowy Ghost of Despair slinked across the room, pulled back the sheets, and crawled in next to me.

A bony arm reached across my chest and pulled me in close. A new relationship was forged . . . 👊

#SOYCD

B.B.P.S. - Are you the Christian parent of an LGBTQ child? I’ve started an online support program just for you. You can learn more here.

All photos by Sterling Graves. Copyright Blue Babies Pink & Sterling Graves.

B.T. Harman is a former marketing executive turned creative strategist, podcaster, and speaker.

Today, B.T. is a freelance content creator for millennials and the brands that serve them. His consulting work focuses on brand strategy, design, marketing, social media, leadership, and more.

He is also the creator of the blog & podcast, Blue Babies Pink, a personal memoir of growing up gay in the American south. More than 1.3 million episodes of the BBP podcast have been streamed since its debut in 2017, and it was a top 40 podcast worldwide in March of that year.

B.T. recently released his second narrative-style podcast, Catlick. Catlick is a historical true crime saga that follows a tragic series of events in early-1900s Atlanta. In 2020, cnn.com included Catlick as a "must-listen podcast." Since its debut, Catlick fans have streamed more than 450,000 episodes.

Before launching his career as a freelance content creator, B.T. was Vice President of Client Experience at Booster, an innovative school fundraising company based in Atlanta. Between 2005 - 2016, B.T. was a key player in helping Booster raise more than $150 million for American schools. Within Booster, B.T. managed a team of creatives that developed high-end character and leadership content for more than 1.3 million students annually.

B.T.’s other interests include storytelling, leadership, good design, antiques, the Camino de Santiago, SEC football, European travel, Roman history, archaeology, and Chick-fil-A. He also serves as the board chairman for Legacy Collective and as a board member for BeLoved Atlanta.

B.T. lives in the historic East Atlanta neighborhood with his husband, Brett.

And to get to know B.T. better, check out btharman.com.